In the Sherlock Holmes stories, Conan Doyle describes the Diogenes Club as a place where odd and unsociable men go only to read the latest periodicals, all talk being forbidden. This was an exaggeration, but under the circumstances, the Club felt it was better to leave well enough alone, rather than risk drawing attention to activities which were, in both government and Club terms, unofficial and often diplomatically sensitive. Now, a century on, there is no longer a compelling reason to withhold the explanation as to what the great interest was in all that reading.

In 1891, a publisher named George Newnes had created The Strand Magazine, which quickly became the regular home for the Sherlock Holmes stories (he having first appeared in Beeton’s Xmas Annual). A self-made man from the Industrial North and a philanthropic exponent of “Muscular Christianity,” Newnes built a publishing empire with titles such as Tit-Bits, a popular-miscellany magazine now classed as a harbinger of ‘the New Journalism,’; the Review of Reviews, whose monthly digests of leading journals and magazines appealed to busy professional men; the Westminster Gazette (an evening paper printed on green paper); Country Life; and The Captain, one of those youth periodicals meant to inspire ideals of sportsmanship, fair play and Empire. (A Liberal MP from 1885 on, Newnes became Sir George in 1895, and a country gent with an estate in North Devon.)

Since 1891, The Strand Magazine has been the title familiar to Holmes fans the world over, but from it would come a longer-running spin-off, to which Club members frequently contributed, it soon becoming the most requested title in the Club library. This was The Wide World Magazine, which survived (later as plain “Wide World”) until 1965, outlasting The Strand by 15 years. Throughout the 1890s Newnes kept receiving articles from all around the world on travel adventures, colonial experiences, and the like, which didn’t fit in with The Strand’s cosmopolitan mandate. Such true-life outdoor adventure stories did find publication in other periodicals, but there was no magazine dedicated to suchlike. Thus in 1898 was born The Wide World Magazine, subtitled 'The Magazine for Men'. It has to be said this was nothing like the later American pulp men’s magazines, whose covers featured red-blooded action heroes and blondes in revealingly-ripped underwear, in some type of jeopardy such as Nazi torturers or crazed beasts.

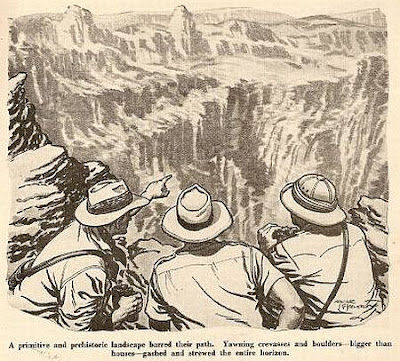

WWM contributors included authentic explorers like the African explorer Stanley, and keen-minded travellers like Conan Doyle himself, who had wide-ranging interests. Most were amateurs contributing a single article on their experiences abroad, and each issue had articles describing first-hand experiences all over the globe (helpful diagram map provided each issue). Club members would lap up articles like ‘Queer Scenes in Sumatra’, ‘The Hasheesh Smugglers Museum’, ‘Savages At School’, ‘How We Hid The Nihilist’, ‘Klondike Pictures’, ‘The Queerest Fire Brigade In The World’, ‘Rock Climbing In Great Britain’, ‘Across Europe Without A Passport’, ‘The Motor Cab School’, ‘My Cycle Ride To Khiva’, and ‘How I was Buried Alive.’ These are all examples from a single bound volume, representing the first half-year’s worth.

The magazine’s commitment was to strange-but-true stories, but from the outset it was beset by the problem of verifying whether any given submission was indeed true, and they were soon the victim of hoaxes. The very first year, WWM’s ‘How I was Buried Alive’ by one Baron Corvo, proved the work of a now-famous literary fantasist, Frederick ‘Hadrian VII’ Rolfe. The same year was the more spectacular case of the self-proclaimed ‘King of The Cannibals’ who in a year-long series of WWM articles told how after being marooned off NW Australia he had spent 30 years among the aborigines. Newnes got the Royal Geographic Society to agree to sponsor talks by the author, Louis de Rougemont, and circulation soared. However certain details (like a reference to flying wombats) made knowledgeable club members suspicious, and they alerted Newnes, who foolishly tried to brazen it all out. The author soon proved to be one of those types who reinvent themselves every year with some new scheme, and was known to the Australian police as Louis Grin. It turned out Grin had added to his knowledge by spending time in the British Library Reading Room – something that helped convince the Club Secretary to stock all the major periodicals – not just The Wide World.

Newnes personally brought over a selection from his publishing empire for the Secretary to peruse. Of course it was Wide World that was most avidly read, with its focus on expeditions to remote territories – and the fact Club members would often know the authors. They would sit there for hours over a pot of coffee, entranced by accounts like “Exploring The Skeleton Coast,” “Australia's Mounted Police,” and “Killer Cats Of British Columbia” (to use 3 examples from one issue). The Reading Room, which was not large, would soon fill up, and even the front lounge was given over to reading rather than talking. The quite clubbable Conan Doyle had visited the Club one day in 1890 (the Secretary wanted him to join) and saw this for himself, later calling this behaviour “queer” in print. (The great man joined several other clubs, including the most prestigious, the Athenaeum.) Club members, who were often self-educated, self-made men like George Newnes, clearly did not think so, but did not try to change this view.

One reason for being circumspect was that in those days, travels to remote districts were often a cover for intelligence work. Too often, travellers who kept diaries and sketchbooks or took photographs were arrested as spies, and some indeed were. Newspaper tycoons would openly finance expeditions with political ambitions, and even try to stir up colonial wars. (Many readers will be familiar with US tycoon William Randolph Hearst’s role in helping foment the Spanish-American War of 1898, and Evelyn Waugh’s satiric novel Scoop, based on his experience as a war correspondent in 1930s Abyssinia.) Similarly on the exploration front, Stanley’s explorations to find Dr Livingstone were backed by a newspaper (Gordon Bennett’s New York Herald), which led to the Belgian king offering him a chance to run the Congo as a slave colony.

Over the years, there were endless press-involved expeditions to remote regions from Asia to the Poles - any of which might lead to a diplomatic claim to the territory, accusations of spying, and possibly even a war with rival powers. In 1898, to help kick-start WWM, Newnes had financed an Antarctic expedition, after the Royal Geographical Society spent years in political wrangling over details, and had himself filmed seeing the expedition off. Ironically, the news was knocked off the front pages by sensational tales of the hoaxer Louis de Rougemont, by then taken up by other newspapers. But there would be another six decades of Wide World expeditions, some no doubt with covert backing – and the help of other well-placed Club members. For a long time “DC” was not used just the Club’s initials, but was short-hand for “Decent Chap” – a man you could trust with your life (and who wasn’t afraid to smoke a pipe either).

A few of these Club-backed expeditions have become legendary within the Club portals, and now the protagonists are all safely dead, perhaps we can recount a few tales someday soon... Such behind-the-scenes arrangements have mostly never come to light since the archives of Wide World, which included correspondence with many great men of the time, mysteriously disappeared during WWII, after they were put in “deep storage” during the 1940 invasion scare. Perhaps it is no surprise they never resurfaced. There would have been Whitehall concerns that colonial history would have to be rewritten in places. Even today, the entire clutch of issues raised by the WWM - what was real, what was propaganda, who was financing an expedition, what its real aims were etc - remains touchy. The compiler of a recent reprint-anthology (an English lecturer described as “long obsessed with the treasure trove of Wide World Magazine”) had to use a pen-name to protect his identity, and his anthology, published by Macmillan, vanished from print so quickly that searching for it on Amazon showed no results.

Another sensitive factor was the secret existence from 1898 to 1948 of the WWB – The Wide World Brotherhood, set up 'to treat fellow members as brothers and, if need arises, give them any help possible'. Until 1949, the WWB was kept a secret from ordinary readers, known only to contributors. Among these were of course many Club members, who were able to use it when in remote ports, on expeditions and cruises often diplomatically sensitive and not officially supported. After 1949, the WWB was turned into an organisation open to any reader who undertook its guiding principle of helping other Brothers as “a solemn pledge.” The magazine explained “The WWB is a fraternity of men and women of goodwill, linked by the common bond of a love of travel and adventure.” The magazine also published looking-for-pen-friends lists, so members could contact one another.

There was no fee, the only cost 5 shillings for a discreet gilt and enamel buttonhole badge to identify oneself to others in the Brotherhood. There was a brooch for lady members, of whom there were soon a surprising number (it turned out they were being encouraged to join by love-starved bachelor Brothers.) These identification pins could of course be worn strict school-uniform style, i.e. on the underside of the lapel, if discretion was wanted. You also got a certificate of WWB life membership, and could also purchase a pure-silk WWB tie (British-made, of course) and silk ‘muffler’ cravat. There were also heraldic-style shields and seals that could be variously mounted around den or office. Motoring members could obtain a windscreen sticker and a pennant that bolted onto the radiator cap.

Throughout the century, the world became less and less an unknown region, and soon the magazine became more for the armchair ‘adventurer’ (and today, a nostalgic collectable). The WWB developed a domestic version, becoming the basis of small local social groups here in England. They would meet in corners of quiet pubs and go on modest outings by motor car into the depths of the countryside - much as we still do today.

No comments:

Post a Comment