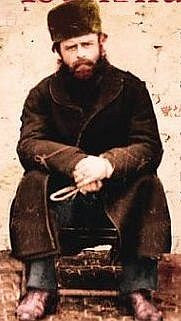

One of these was a British explorer who came to be called by his biographer “the last great imperial adventurer”. His brash early geographic explorations through the heart of Asia led to him later exploring his own heart for the lessons that might be learned from the ancient wisdom of the East.

Although born in India, he was packed off back to England to be raised by two religious aunts. After attending Clifton College in Bristol, Francis Younghusband joined the Army for the same reason many did at that time – the opportunity for adventure abroad. Inspired by his uncle, a noted explorer of Central Asia, Younghusband became in 1886-7 the first European since Marco Polo to cross China and Asia. The young subaltern travelled through Manchuria to Peking and into Mongolia, crossing the Gobi Desert and the Himalayas to India. For this remarkable feat, the Royal Geographic Society not only gave him a gold medal but elected him as their youngest member, age 24.

He transferred to the Political Service and got involved in what Kipling in his novel Kim would call "The Great Game." This was the contest between Britain and Russia for political control over the lands beyond India’s North-West Frontier. After discovering the source of the river after which India is named and nearly having war with Russia break out when he was reported killed, Younghusband was despatched to Tibet at the head of British military mission.

He transferred to the Political Service and got involved in what Kipling in his novel Kim would call "The Great Game." This was the contest between Britain and Russia for political control over the lands beyond India’s North-West Frontier. After discovering the source of the river after which India is named and nearly having war with Russia break out when he was reported killed, Younghusband was despatched to Tibet at the head of British military mission.In 1904, his friend Lord Curzon, Viceroy of India, sent him in to show the flag as part of the political Great Game. There in his zeal, Younghusband exceeded his instructions, leading to the massacre of a Tibetan militia army. In the capital Lhasa, he intimidated the Dalai Lama into signing an impromptu anti-Russian alliance treaty with Britain (later repudiated by an embarrassed Whitehall, which was pretending neutrality). But while his men looted the Potala Palace and the monasteries, his own time in Tibet became the turning point of his life. In the mountains he had a spiritual experience, a mystical revelation about the oneness of humanity and religion, which would change his formerly evangelical-Christian outlook into an Oriental mystical one. (In Whitehall parlance, they called this ‘going native.’)

Although invested with the title of Knight Commander for his “conquest” of Tibet, Sir Francis turned from the sword to the pen, becoming a writer and propagandist for his beliefs. Instead of serving the cause of Empire, he felt he would instead serve the cause of humanity’s spiritual development. During the First World War, he sailed to America with Bertrand Russell to lecture in philosophy. He then commissioned the song which would become Britain’s popular “alternative” anthem, Jerusalem, based on Blake’s mystical verse, but refused to let it be used to promote wartime jingoism. (He even thought the Boy Scouts too militaristic.)

After the war, he became President of the Royal Geographic Society, and organised several reconnaissance expeditions following his 1904 Tibet route, this time right across Tiber to the Chinese border to explore Mt Everest, named after a British official, but known more reverently by Tibetans as Chomo-Lungma, the ‘Mother Goddess Of The World.’ It was on one of these expeditions to the “roof of the world” that two famous colleagues of his failed to return, their fates a mystery, when Mallory and Irvine vanished near the summit in 1924. He himself turned to inner exploration, and became a mystic admired by Bertrand Russell and HG Wells. He explored esoteric ideas like telepathy and the existence of superior extraterrestrial life forms, writing a score of books on spiritualist beliefs which anticipated those of the 1960s, with titles like The Heart Of Nature (1921), Mother World (1924), Life In The Stars (1927), and The Living Universe (1933).

In 1936, he attempted to reduce religious differences by establishing the World Congress of Faiths as war clouds again gathered over Europe and Asia. (His former house-maid Gladys Aylward was caught up in this, she having become a missionary in China just before the Japanese invasion, an event depicted in her filmed biography, The Inn Of the 6th Happiness.) The American aviator Lindbergh, an antiwar activist also interested in matters spiritual after the kidnapping and death of his baby, personally flew him across India, whose independence he long supported. But though he admired Gandhi, he was not entirely ascetic. In fact, he also preached free love, criticizing marriage as an outdated custom. Until his death, he lived with Lady Madeline Lees, who with her husband had co-founded a Christian commune at South Lytchett Manor in Dorset. Having forsaken his wife, he spent part of his last few years with his much younger companion at her manor house on the north side of Poole Harbour. He died at the Manor during WW2, of a stroke.

You can visit his grave in the quiet country churchyard of Lytchett Minster, across the fields from the Manor, next to an ancient yew tree and under a headstone with a carved image of the Dalai Lama’s palace in Lhasa.

You can visit his grave in the quiet country churchyard of Lytchett Minster, across the fields from the Manor, next to an ancient yew tree and under a headstone with a carved image of the Dalai Lama’s palace in Lhasa.

No comments:

Post a Comment